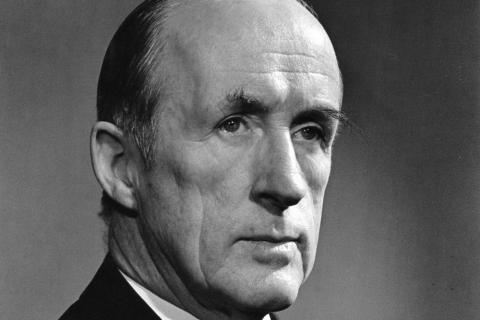

Archie Mackenzie, one of the last surviving founder members of the United Nations at its birth in 1945, became a senior diplomat at the UN in New York in the 1970s, where he was Britain’s minister for economic and social affairs. A man of profound moral conviction, he held an abiding belief that the UN, for all its shortcomings, could play a decisive role in world affairs, including generating the necessary “political will” to address global economic disparities.

He was Britain’s spokesman at Dumbarton Oaks in 1944, which drew up the UN’s charter, and headed Britain’s press relations office at the San Francisco Conference in April 1945. This led to the final drafting of the charter, signed there by President Truman. Mackenzie was then on the preparation committee of the UN’s first General Assembly, held in the Methodist Central Hall, Westminster, on January 5, 1946.

At the UN’s new headquarters in New York, he was appointed First Secretary with special responsibility for public relations. He served under the UK’s first UN representative Sir Alexander Cadogan. Mackenzie developed excellent relations with the press, the New York Post’s correspondent writing: “Mackenzie has become celebrated as the author of more good news breaks than any other single source in the United Nations corral.”

But it was nearly three decades later that Mackenzie played his most influential role at the UN, when he was the British Representative on the UN’s Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), the sister organisation of the Security Council, from 1973 to 1975. It was the time of the first oil shock, when the 13 oil-producing nations of Opec oversaw a huge oil price rise. Developing countries, hit as hard as industrialised ones, began to demand a new international economic order. The Western countries were roundly defeated at the vote of the Sixth Special Session of the UN General Assembly, called to deal with the oil crisis, which, in Mackenzie’s words, had produced “seismic shudders” in the UN.

Britain found itself isolated from many Commonwealth countries, and Mackenzie realised that the UK needed “a fundamental rethink of our position” before the Seventh Special Session in 1975. He was fortunate to have Ivor Richard, by then head of the UK’s mission in New York, supporting him in this, as well as senior advisers to James Callaghan, the Foreign Secretary, in Whitehall.

A critical moment, Mackenzie realised, would be the opening meeting of the Preparatory Committee, “to convince the developing countries that we had something new to say” about the afflictions they faced. In his opening speech, he addressed the need to “cross the philosophical bridge of change”. The phrase caught everyone’s attention and was often quoted afterwards. The Seventh Special Session turned out to be particularly successful in setting the UN on a new path of awareness of the concerns of the developing world. A few weeks later, much to Mackenzie’s surprise, the Yugoslav delegate to ECOSOC, representing the non-aligned countries, intervened by prior arrangement to make a moving tribute to Mackenzie: “With him arrived a new spirit and a new attitude of his country towards ECOSOC and the solving of international economic problems.” Mackenzie’s role on ECOSOC was the pinnacle of a diplomatic career that had taken him to Cyprus (1954-1957) as information officer; Paris (1957-1961) to be involved in the founding of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; Burma (1961-1965) as the UK’s Commercial Counsellor in Rangoon, coinciding with a military coup; Zagreb in Tito’s Yugoslavia (1965-1970) as the British Consul General accredited to Croatia and Slovenia; and as Ambassador to Tunisia (1970-1973). None of his posts was the top position that a man of his abilities might have expected. The reason was undoubtedly his lifelong association with the Moral Re-Armament movement, which brought him under suspicion in some Foreign Office circles.

Archibald Robert Kerr Mackenzie was born in 1915, in Ruchill, Glasgow, the son of a banker. Attending Sunday School, he gained 100 per cent five years running in the nationwide Bible exams of the United Free Church of Scotland. In 1933 he entered Glasgow University where he gained first-class honours in mental philosophy. Immanuel Kant became the inspiration for his philosophical outlook. From 1937 he studied Modern Greats at The Queen’s College, Oxford, where he also linked up with Frank Buchman’s Christian movement the Oxford Group, the forerunner of Moral Re-Armament.

In 1939 he was awarded a two-year postgraduate Commonwealth fellowship, sponsored by the Harkness Foundation, to study in America. This took him to Chicago University for a year and then to Harvard in 1940.

From Harvard, Mackenzie’s inside knowledge of the American scene made him a suitable candidate for recruitment by the British Embassy looking for extra staff in Washington as war broke out in Europe. It was imperative that the Foreign Office received daily, even hourly, reports on US attitudes towards, and media coverage of, the war against Hitler. In this role, Mackenzie worked for three years in the embassy as “Man Friday” to Isaiah Berlin, the distinguished philosopher and Oxford don. On retirement from the Diplomatic Service in 1975, Mackenzie and his wife, Ruth, moved to a cottage on the shores of Loch Lomond. Two years later, Edward Heath invited him to be his assistant on the Brandt Commission on international development issues. Mackenzie was one of the five-person team that drafted the final report.

He is survived by his wife Ruth.

Archie Mackenzie, CBE, diplomat, was born on October 22, 1915. He died on April 15, 2012, aged 96

First published in The Times, 3 May 2012