This article by Michael Smith first appeared in The Guardian on 18 February 2005

Zimbabwe, once the breadbasket of southern Africa, has seen such a collapse in its agricultural base that over 5 million people will need charity to prevent starvation by the end of the year, according to the UN's World Food Programme. President Robert Mugabe's land reforms have seen a dramatic drop in commercial maize production, leaving 38% of the population undernourished.

Poor harvests in 2002 and 2003 left millions of people needing food assistance. Last year Zimbabwe's farmers planted only about a third of their usual fields and the World Food Programme has designated Zimbabwe as a "hunger emergency zone". Food will be a major issue during the presidential elections scheduled for next month.

Yet small-scale farmers are not without hope. They are benefiting from "born again" sweet potato plants, developed by a team of Zimbabwean scientists. The eight agricultural graduates are employed by Agri-Biotech, founded by Edinburgh-born scientist Dr Ian Robertson, the company's chief executive, who teaches agriculture at the University of Zimbabwe. The plants make it possible for a 30-metre square plot to feed a family of seven all year. Over 30,000 people have benefited in the past two years. And that's just the beginning: so far the company has covered eight of Zimbabwe's 56 districts, chosen by the Zimbabwe Farmers Union.

The Agri-Biotech team call the plants "born again" because they have found a way of removing the virus that plagues sweet potato crops. In a GM-free tissue culture process, they employ cutting edge science literally. They dissect out the 0.25mm tip of the bud, which is free from viruses and other micro-organisms, and throw the rest away. The lab team then grows the bud tip in a test tube for nine months into a virus-free plant, and keeps on sub-culturing it to increase numbers. From there they transplant the plants into plastic greenhouse tunnels and take cuttings from them. These are bought by donors, such as the Swedish Cooperative Centre (SCC). The Stockholm-based NGO is funding Agri-Biotech to supply 3,000 starter plants to 160 nursery farmers. "We need good lab work plus good greenhouse work to deliver to good farmers," says Robertson, a specialist in plant tissue culture.

Unfortunately the virus cleansing is not permanent. "The clean plants will inevitably pick up new viruses and degenerate," says Robertson. "Farmers come back to us for new clean material every few years." The starter plants grow in August, and are irrigated during the following months of sunshine. Many resettlement farmers have access to a well, stream or irrigation system. Each of the 160 farmers can then sell the runners to over 100 neighbours in time to plant for full growth during the rainy season, which starts in December. Meanwhile the nurserymen lift the virus-free sweet potato tubers and sell them early when prices are good, at a time when neighbours are growing for "stomach-fill" for their families. Nothing is wasted. Tubers that are too small or too big to sell at the market, or are damaged by insect pests, are fed to cattle.

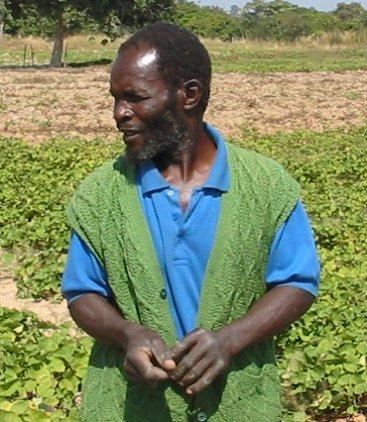

Boy Ncube (right) was one of 20 nurserymen who were trained, over three days, in nursery management and field production by Agri-Biotech's liaison officer Reuben Tayengwa. Agri-Biotech then supplied Ncube with 3,000 cuttings of Brondal sweet potato as well as 200 stakes of Zambezi cassava. With the help of organic fertiliser, Ncube grew vines to sell. Over two years his 30-metre square plot expanded to three hectares. He has turned his initial delivery of $150 into sales of $16,000. This has allowed him to buy a cow and he is building a house, and will buy a "bakkie" (truck) to carry his tubers to market. His best field has yielded 50 tonnes per hectare, compared with the national average of six tonnes.

Nicholas Chimbwedza started farming 2.5 hectares of Brondal two years ago. Selling vines, fertilised with cattle manure, earned him $150. He has started harvesting tubers from just 0.16 hectare and has earned $1,000. This has enabled him to buy a new pump for his field. He expects to earn over $15,000.

Dickson Gumede has 0.32 hectare and expects a harvest of eight tonnes on a yield per hectare of 25 tonnes.

In the current emergency SCC has contracted Agri-Biotech to deliver 1,000 plants each to another 1,000 "beneficiaries": disadvantaged orphans, old people who have lost their "middle generation" to HIV/Aids and single parents. In two years, thanks to Agri-Biotech's research and donor funding of some $300,000, the farmers have cashed in $1.2m. The company itself has made only $50,000 but it has employed eight graduates.

The UK's Department for International Development is "very impressed with the excellent work and dedication of Ian Robertson and his team", says Tom Barrett in DFID's Zimbabwe office. DFID has developed a programme in collaboration with several NGOs and Agri-Biotech that will distribute the improved sweet potato planting material to as many as 2,000 of the poorest households in Harare. Care, with DFID funds, also has a programme that should reach 2,000 rural farmers in Masvingo province. For further information: email agbio@mweb.co.zw

Ian Robertson died suddenly from a heart condition on 1 August 2021.