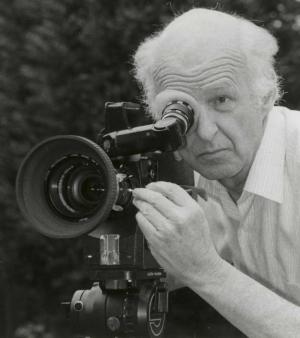

The photographer and film-maker David Channer devoted his life to making films about reconciliation and forgiveness. His sensitive approach enabled him to get alongside people who would not normally have allowed their stories to be told.

His company, FLTfilms, derived its initials from one of Channer’s most enduring films, For the love of tomorrow (1986), about the life of the French Resistance leader and post-war parliamentary deputée Irene Laure. She had “willed the total destruction of Germany” because of her son’s suffering at the hands of the Gestapo, but went on to work for Franco-German reconciliation after a profound experience which enabled her to forgive. The pain of her experiences made Laure reluctant to sanction any film about her life, but Channer inspired her to do so “for the love of tomorrow”. The film was dubbed into 17 languages and broadcast in countries as diverse as Lebanon and the United States.

This same sensitivity had enabled Channer to make his first important documentary 14 years earlier, a portrait of William Nkomo, founder of the ANC Youth League and an eloquent campaigner for racial justice in South Africa. Few people thought it possible for an Englishman to make a film of a black nationalist at the height of apartheid, but Channer’s personal rapport with Nkomo, as with the subjects of all his films, won through.

David De Renzy Channer was born in Quetta, India, now in Pakistan, in December 1925. His father, Major-General George Channer of the 7th Gurkha Rifles, was Deputy Adjutant General of the Indian Army and ADC to King George VI. His great grandfather, Sir Annesley De Renzy, was Surgeon-General of the Indian Army.

Channer came to England at the age of eight. He was educated at Wellington College and commissioned into the Royal Engineers in 1944. He passed out first of his course at the Ripon Officer Cadet Training Unit, and was sent to Cambridge University for six months before returning to India in November 1945. He joined the Bombay Sappers and Miners in Poona (now Pune), rising to the rank of Captain.

Field Marshall Sir Claude Auchinleck, Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Army, now invited him to be one of his ADCs. Channer’s response to this offer was a turning point. Possessing a deep Christian faith, he had become interested in the ideas of Moral Re-Armament (MRA), the international movement founded by the Lutheran minister Frank Buchman. He turned to his practice of taking time in silence to seek God’s inspiration, and after consulting an Indian friend, decided not to take the post but to leave the Army altogether.

In 1947, he sailed to America, where his interest in photography led him to join the press team covering the work of Frank Buchman, under the leadership of Arthur Strong, whose portrait of C.S.Lewis hangs in the National Portrait Gallery.

Channer’s photographic talents were noticed by Tom Blau, founder of Camera Press, who became something of a mentor. Channer’s pictures of Nasser, Nehru, U Nu, U Thant, Diem, Buthelezi, Indira Gandhi, JF Kennedy and the young Saddam Hussein were published in newspapers worldwide.

In 1956 Channer married Kirstin Rasmussen. They spent much of their early married life in India, where Channer first tried his hand at documentary film, encouraged by Rajmohan Gandhi, a grandson of Mahatma Gandhi. Twenty-five years later, he profiled Rajmohan Gandhi himself in Encounters with Truth (1990), which was screened at international film festivals and broadcast across Asia.

During his years in India and South-East Asia, Channer became drawn to the philosophy and meditative practice of Buddhism. He returned an ancient Tibetan tanka, which had come into his possession through a family friend, to the Dalai Lama as a gesture of restitution for British misdemeanours in Tibet.

Channer’s three films on Cambodia stemmed from his friendship with Renée Pan, the widow of Pan Sothi, Minister of Education in the Lon Nol Government, who disappeared in the Khmer Rouge killing fields. After seeing For the Love of Tomorrow in the United States, she contacted Channer and urged him to make a Khmer version to help foster reconciliation in Cambodia at the time of the UN-sponsored elections in 1993.

Channer went on, with his son Alan, to make The Serene Smile (1995) and The Serene Life (1996), on the role of Buddhism in Cambodia’s post-genocide and post-war recovery. The Serene Life contains the only full-length interview given to a professional film crew by the Patriarch and Nobel Peace Prize nominee Venerable Maha Ghosananda. More than 1000 video copies of these films were distributed by international donor agencies throughout the country. His third Cambodian film, The Cross and the Bodhi Tree (2001), explored the encounters with Buddhism of a French Catholic priest and an English Anglican nun. It was endorsed by The Vatican “as very powerful… very helpful in our dialogue.”

By now Channer had trained a succession of budding film-makers, who were sometimes baffled by his combination of military briskness and Buddhist tranquility. As an Australian production assistant put it, “It was difficult to keep pace with this commander. I never knew whether to gather the troops, watch the grass grow or order another five copies of a video in Swahili.”

Channer celebrated his 80th birthday last year, shortly after returning from northern Nigeria where he and his son were working on what would be his last film, The Imam and the Pastor. Due to be premiered at the UN in New York on November 28th, and launched in Parliament in London on December 6th, it tells of the peace-making work of Imam Mohammed Ashafa and Pastor James Wuye, once bitter enemies.

The crucifix hanging above Channer’s bed in the hospice where he died was given to him by a Muslim from Palestine.

David De Renzy Channer, photographer, cameraman, film director and peace worker: born Quetta, India, 18 December 1925; married Kirstin Rasmussen 1956 (one son); died London, 15 September 2006.

First published in The Independent on 28 September 2006